The security guard, patrolling a corporate campus, spots a broken window and records their assessment. Following a pre-defined checklist, the guard finds a footprint in the broken glass inside the building, which warrants escalation: the guard to their superiors to detectives to the organization’s leadership. Following the trail of evidence, the detectives reach a locked safe. Did the safe work and deter the thief? Was the thief able to bypass the safe and get what they wanted? Is the corporation able to enumerate everything that was in the safe?

Regardless of the outcome, the story resonates as a reasonable approach to physical security and response given that we have dealt with this type of scenario for a very long time.

So why is this so difficult within the cyber domain?

Many companies overcomplicate their incident response programs when the approach should be as direct as the story above.

Stepping out of the fire of reactive response to think systematically about the structure and rigor of an operational program is when you can define an approach that is more efficient right of breach (after) and more effective left of breach (before). To get you started let’s:

- review Jargon

- explore the Principles of Threat Detection

- define the Roles of an Incident Response Team

- review Why Hunting Matters

- classify the Content required

- present Next Steps

Before proceeding with program building it is important to have a foundational understanding of common terms.

- CSIRT. Computer Security Incident Response Team that handles any security incident bypassing security controls.

- SOC. Security Operation Center handles administration and monitoring of security controls (firewalls, IPS, endpoint protection, DLP, etc.).

- Event. Anything that happens within the computing environment (e.g., log records, network sessions, file changes, permission changes, privilege escalation, command execution, memory changes).

- Requires collection

- Incident. An event or collections of events with indicators that align with your threat priorities. A physical example would be a broken window.

- Requires investigation leading to remediation or escalation

- Major Incident. An incident with the potential for loss or harm.

- Requires leadership notification.

- Breach. An incident with evidence of loss or harm.

- Requires activation of Executive Response plan with public and/or customer notification

1. Business Defines Risk

Task: Create Risk Register with Threats and Critical Assets

This critical step shapes the rest of your plan. This is where you understand what assets need to be protected and why, as well as the basic information needed to understand mitigating threats to those assets.

2. Threat Intel Defines Controls and Priorities

Task: Align Controls to Mitigate controllable ThreatsTask: Cultivate Threat Intelligence for remaining Threat Priorities

When presented with 10 active threats and you have capacity for two, where do you start? Threat prioritization is critical to your success. If you can implement a security control to mitigate your Threat Priorities, do it. Things like Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), Risk-Based Authentication, Network Segmentation, IPS, Firewalls, and so on are all great ways to reduce the number of threats you must hunt for.

Next, determine how best to get information on remaining Threat Priorities not mitigated by controls. Identify open source feeds, paid subscriptions, information sharing – anything that will help you be aware of how these threats behave, when they are active, and how they might show up in your environment.

3. Establish IR Plan around your Threat Priorities

Task: Develop Use Cases for your Threat Priorities

Conduct threat analysis on the information gathered in the first two steps to define detailed use cases. These use cases identify the nature of the threat, stakeholders, the critical assets likely to be affected, the types of content needed to detect an active threat, as well as the associated logic to detect it, and guidance on prioritization and workflow.

With this level of understanding you can better structure the team and develop communications and incident management workflows; enabling you to build an IR plan to manage the chaos.

4. Operationalize Incident Handling

Task: Combine your Use Cases into Playbooks

Use the IR Plan to establish response procedures and operationalize use cases into actionable playbooks primary incident handlers will execute against daily. This addresses all threat priorities detected through structured logic, correlation, and investigation.

5. Hunt Daily

Task: Hunt for Anomalies that exist outside your playbooks

Any threat priorities not covered by playbooks will require hunting. This is where the most critical detection and response activity occurs. This is the stage where zero-day exploits are found and the anomalous activity that bypasses both defense-in-depth and operational rigor occurs. Hunting is continuous and constantly informed by emergent threats and new developments within the threat landscape.

6. Commit to Continuous Improvement

Task: Review incidents quarterly and critical incidents directly

Task: Exercise playbooks through Simulation/TTX for readiness

Task: Assess resilience to threats with Gap Analysis

Once the program is established (steps 1-5), it is time to reinforce skills, orient new staff and train on any new use cases or threats identified. On-going use of tools, such as gap analysis, helps track overall progress and identifies additional improvements needed.

Roles of an Incident Response Team

With the principles of threat detection outlined it is time to turn to the core roles of a successful incident response team. Understanding how these functions perform is critical to assessing where you are in your security journey.

The Threat team focuses on managing threat intelligence. They identify the data feeds required for information on threats and which records within those feeds are valid.

The Content team leverages threat intelligence reports to refine the use cases necessary to detect the presence of threat priorities and build the associated playbooks. This includes defining rules, building parsers, configuring alerts, and documenting response procedures, as well as tuning the detection strategy to minimize false positives.

The Playbooks (triage) team, executes against the standard procedures, validating any alerts, and escalating to the hunting team if the playbook does not result in a path to remediation. Most incidents are handled at this level (in a large organization, 60-90 incidents per day is not uncommon).

The Hunting team spends most of the time on proactive investigations, looking for anomalies or following new threat intelligence as shared by the threat team. Hunters are also responsible for investigating incidents that cannot be resolved via playbook. Major incidents are handled at this level and should be rare (in a large organization, 4-5 major incidents per year is considered normal). Findings from the hunting team’s investigations are shared with the threat team to determine how it is recorded or shared with the content team.

These roles are necessarily separate from current security device and network administration teams. This is critical. The device and network administration team spends its time maintaining firewalls, core networks, AV systems, or servers. As such, they cannot also investigate incidents, manage threat intelligence, tune content, or hunt.

These roles may represent a fraction of a full-time employee or multiple team members, but the functions are critical to a comprehensive IR strategy. In smaller teams, cross-training team members to avoid single points of failure enabling some degree of consolidation. With a lean approach, a small team might consist of four members:

- two who split their time between threat and content

- one hunter

- one who splits their time between hunting and playbooks coordination

The trick then is to staff the Playbooks team 24×7, or even 8×5. This is where managed detection and response (MDR) providers can help.

Managed Detection and Response

You can outsource the Playbooks role to provide 24×7 incident triage by partnering with a managed detection and response provider (MDR) if you have well-defined playbooks. MDRs deliver value by executing playbooks rather than the traditional log aggregation and alert hand-off provided by a traditional Managed Security Services Provider (MSSP), thus alleviating the burden off the in-house team for round-the-clock staffing. The in-house team’s focus is then on threat intel, content analytics, and hunting.

Unfortunately, hunting can never be fully outsourced. Third-party providers simply cannot understand the environment as well as the in-house team, thus requiring at least one person in-house capable of handling playbook escalations and anomaly detection (the hunter described above). They should spend most of their time looking for suspicious activity within the environment.

Retainer and Surge Response

It may prove useful to further round out capabilities with an incident response retainer. This is separate from an MDR provider who typically does not provide advanced forensic capabilities.

The expert resources available on retainer enable you to add resources to deal with a major incident while ensuring your existing team can continue with their daily operational responsibilities.

A common threat actor tactic is to create a noisy event to mask a far subtler one. The in-house analysts need to continue with daily tasks while the expert resources investigate as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Ultimately, understanding how these roles map to the staffing model is critical to developing a sustainable operations plan.

Remediation

NIST 800-61r2 outlines the major phases of the incident handling process as Preparation, Detection and Analysis, Containment, Eradication, Recovery, and Post-Incident Activity. However, while the IR team defines the remediation strategy during the Containment phase, it is the IT organization that executes the remediation strategy during the Eradication and Recovery phases.

While remediation is technically part of the NIST guideline on incident handling, incident response teams should not conduct remediation. This is critical. An operational IR team must focus on playbook execution, hunting, threat intelligence, and content analysis. There is no time for managing firewall policy, modifying servers, rebuilding desktops, or any other IT or IT security function.

One of the biggest reasons organizations fail to implement a successful incident response program is because they approach it as an additional duty for their IT or IT Security teams when it is necessarily a separate operational function.

Why Hunting Matters

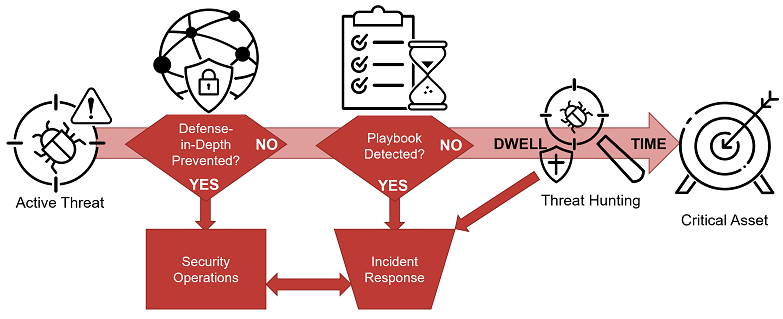

An active threat attempts to exploit a critical asset. Does your defense-in-depth prevent it? Ideally, defense-in-depth prevents the attack using a combination of signature-based solutions, architecture, and blocking—a win for your security operations.

If the attack successfully bypasses your defense-in-depth do you have a playbook in place? A playbook enables the incident response team to detect and respond to the attack—a win for incident response.

However, determined attackers can get past your playbook procedures and progress towards your critical asset. The hunting team should detect the anomalies created by this activity and disrupt the attacker’s dwell time before they complete their actions on objectives.

Hunting is the last line of defense against the most determined attackers—those most likely to cause the greatest amount of damage.

Content

Content is needed to build hunting and detection capabilities and is where many organizations struggle most.

Why is that?

Most often it is a result of competing priorities. Multiple teams within an organization often need the same data but for different, competing business cases, such as compliance, operations or detection and response.

Compliance demonstrates an organization did what they said they would. This information primarily comes from system and application logs and is presented via reports.

Security operations seeks to aggregate security alerts, monitor security devices, and respond to known-bad events with a standard procedure. This information primarily comes from security device logs, sometimes supplemented by netflow, and is presented via alerts and dashboards.

Detection and Response generally deals with all the information outside of Compliance or Operations. Threat hunters interface with an event database to look for anomalies based on context logs, netflow, packets, and endpoint forensic data. However, most log data for the organization is unnecessary for operational incident response.

These competing requirements result in an organization building out content collection around a single business case, limiting or even preventing the other business cases from succeeding. Once an organization understands how its content collection needs can be separated, they can build a strategy to address all business cases effectively. Sometimes this may mean a unified SIEM; other times it may mean a separate log aggregation for compliance from the content collection for detection and response.

Operational incident response is most effective and timely when built on three core elements of content intelligence:

- Context from Logs. Key log data provides visibility into activity on critical systems that inform and frame who, what, where, and when (e.g. IP, MAC address, user account, DNS request, proxy activity, FW/network session, asset criticality, vulnerability/patch disposition, etc.).

- Evidence from Network. Packets contain the truth of how a threat was executed, patterns of activity associated with specific exploits and command and control. Lateral movements can be monitored as well using netflow and packets show what’s happening regardless of what is being logged.

- Proof from Endpoints. Endpoint forensic data is vital for understanding how a threat succeeded. This includes recording kernel processes, privilege escalation, memory manipulation, executable replacement, registry manipulation, and script or shell execution. Most critical is the ability to see this activity in near real time across the entire environment to identify pattern, analyze behavior, and detect any exploit activity.

Combining all three increases the analyst’s speed and efficacy by an order of magnitude. If only choosing two, Packets and Endpoints are the most crucial as they still provide the most visibility into an attacker’s tools, tactics, and procedures.

Next Steps

This is just the beginning but provides a solid foundation from which to build your incident response program. Logical next steps include:

- Complete a Gap Analysis and Roadmap

- Know where you are and be clear about where you want to go.

- Build a Threat Intelligence Program Roadmap

- Understand threat intelligence needs and priorities

- Formalize the Incident Response Plan

- Be clear and direct about how to execute

- Develop Tactical Playbooks

- Start with five threats that can’t be blocked that target the organization’s most critical assets

- Establish an Incident Response Retainer

- Build a relationship with experts that can both advise and assist as needed

- Conduct a Controlled Attack and Response Exercise

- Test the technical and operational capabilities with a simulation

- Conduct Tabletop Exercises

- Introduce or reinforce procedures for new use cases

With the right guidance, you can build a successful operational incident response program in twelve to eighteen months. Focus on quick wins and build incrementally. Target your critical assets, determine the most likely threats to those assets, and then build playbooks around identifying those threats. Once you start executing against these playbooks, expand to new assets and new threats. Every organization is unique, and it is up to you to find the right combination of internal capabilities that leverage external MSSP, MDR, Retainer, and advanced cyber defense services that makes the most sense.

# # #

Visit us to learn more about building an incident response operation.